Seeing the Genesee–Finger Lakes as a Living Bioregion

To look at the Genesee Finger Lakes Bioregion through a bioregional lens is to stop seeing it as a set of counties, cities, or tourist destinations and begin seeing it as a living system—shaped by ice and water, animated by human cultures, altered by industry, and now facing a moment of profound choice. A bioregion is not defined primarily by political boundaries but by watersheds, soils, climate, species, and the long relationship between people and place. When we apply that lens here, a deeper story comes into focus—one that can help the region understand itself, its vulnerabilities, and its latent strengths in an era of climate and economic transformation.

Ice, Water, and Deep Time

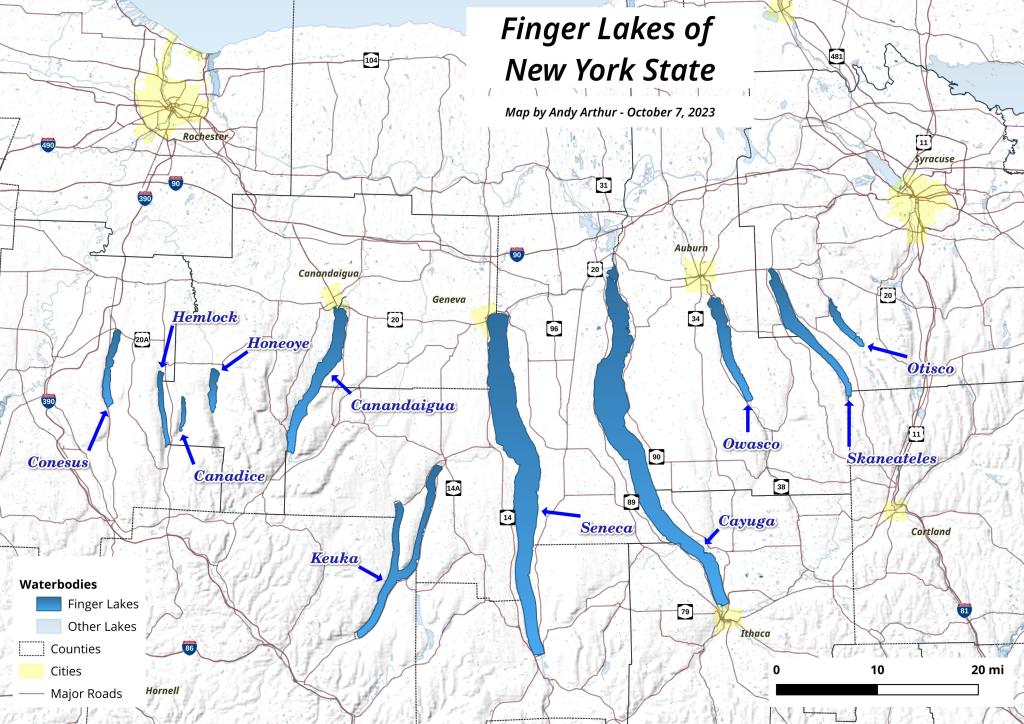

The Finger Lakes owe their existence to ice. During the last glacial maximum, massive ice sheets scoured north–south valleys into the soft sedimentary bedrock of what is now western and central New York. As the glaciers retreated roughly 10,000–12,000 years ago, they left behind long, narrow, over-deepened basins that filled with water, forming the Finger Lakes. These lakes are not isolated features; they are integral components of the Great Lakes watershed.

The Genesee River is the bioregion’s central artery. Rising in the Allegheny Plateau of northern Pennsylvania, it flows north through Letchworth Gorge—sometimes called the “Grand Canyon of the East”—creating majestic and powerful falls before emptying into Lake Ontario. From there, its waters ultimately reach the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River system. What happens on farms, streets, and hillsides in the Genesee basin therefore affects not just local streams, but also feeds into the Great Lakes, one of the largest freshwater systems on Earth.

This hydrological reality is one of the bioregional lens’s first gifts: it reveals interdependence. Nutrient runoff, sediment, industrial contaminants, and stormwater do not respect municipal boundaries. They move downhill, downstream, and outward—connecting upland soils to nearshore fisheries hundreds of miles away.

Indigenous Stewardship and Disruption

Long before European arrival, this region was home to Indigenous nations whose lifeways were attuned to its ecological rhythms. The Haudenosaunee—often referred to as the Iroquois Confederacy—developed sophisticated agricultural systems, governance structures, and ecological knowledge rooted in this land. Their cultivation of corn, beans, and squash (“the Three Sisters”) was both productive and regenerative, enhancing soil fertility while supporting dense populations.

Colonization violently disrupted these relationships. Land was seized, forests cleared, wetlands drained, and Indigenous peoples displaced or confined by European settlers or conquerors. Much traditional ecological knowledge was marginalized or lost, even as settlers benefited from landscapes shaped by centuries of careful stewardship. A bioregional perspective requires acknowledging this history—not as an abstract moral exercise, but because unresolved land relationships and erased knowledge continue to shape present-day ecological and social outcomes.

What we still lack is a comprehensive, region-wide accounting of how Indigenous land management practices altered fire regimes, forest composition, and wildlife abundance prior to colonization. This absence is itself a form of ignorance that limits our capacity to restore ecological function today.

Canals, Industry, and Extraction

The 19th century brought another transformation. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 connected the Great Lakes to the Hudson River, turning the Genesee Valley into a conduit of grain, timber, and manufactured goods. Rochester rose rapidly, powered first by water at High Falls and later by electricity and industry.

The region became a center of innovation—flour milling, optics, photography, and precision manufacturing. Companies like Eastman Kodak helped define Rochester’s identity as a technology hub. But the same industrial success brought heavy ecological costs: polluted waterways, toxic waste sites, and neighborhoods built around single employers.

When global economic shifts and technological change hollowed out much of this industrial base in the late 20th century, the region experienced population loss, disinvestment, and persistent inequality. The bioregional lens makes visible a hard truth: economic decline and ecological degradation often track together, reinforcing one another over decades.

Vineyards, Tourism, and a Partial Renaissance

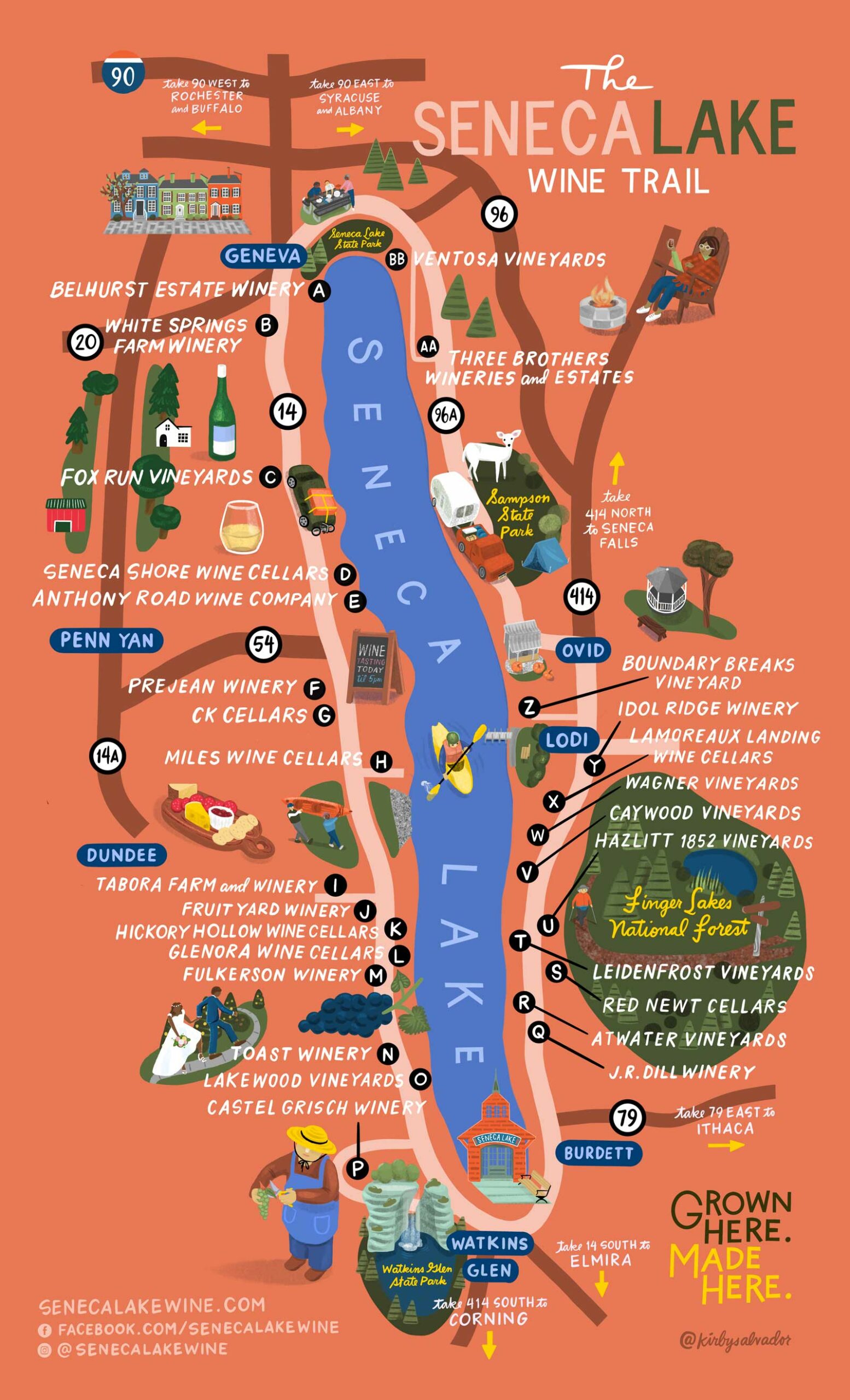

One of the most visible success stories of the region is the Finger Lakes wine industry. Deep glacial lakes moderate temperatures, reducing frost risk and creating microclimates well suited to cool-climate grapes such as Riesling. Vineyards, tasting rooms, and tourism have brought new revenue and global recognition to parts of the bioregion.

Yet even here, the bioregional lens complicates the picture. Vineyard expansion can increase erosion and nutrient runoff if poorly managed. Tourism brings jobs but also seasonal traffic, housing pressures, and infrastructure strain. We do not yet have a clear, publicly accessible assessment of the cumulative ecological footprint of tourism across the Finger Lakes—an example of an important knowledge gap that matters for long-term planning.

Present-Day Bioregional Health: What We Know—and Don’t

Organizations such as Possible Rochester have begun articulating the Genesee–Finger Lakes as a coherent bioregion, emphasizing watersheds, ecological integrity, and social well-being. From existing data, we know several things with reasonable confidence:

- Much of the region’s land area remains in agriculture, predominantly conventional row cropping.

- Wetlands have been dramatically reduced compared to pre-colonial conditions.

- Water quality varies widely: some streams show improvement, while others remain impaired by nutrients, sediments, or legacy pollutants.

- Climate change is already altering precipitation patterns, increasing the frequency of intense rain events and flooding.

What we do not know is equally important. We lack reliable, up-to-date estimates of how much land is under regenerative or soil-building management. We lack integrated indicators that combine ecological health with public health, economic resilience, and social cohesion at the bioregional scale. And we lack shared, accessible tools that allow residents to explore “what if” scenarios—what if wetland acreage were doubled, or riparian buffers restored throughout the Genesee watershed?

Threats, Hazards, and Openings

The region faces real risks: harmful algal blooms in lakes, aging water infrastructure, legacy contamination, habitat fragmentation, and persistent inequality. Climate change adds further uncertainty—more extreme storms, shifting ecosystems, and stress on agriculture.

And yet, the Genesee–Finger Lakes may also be perceived as a relative climate haven: abundant freshwater, fewer extreme heat days than many regions, and a diversified economy with room to evolve. Whether that potential becomes a blessing or a burden depends on foresight. Without bioregional planning, in-migration could intensify sprawl, strain ecosystems, and reproduce old patterns of inequity. With it, the region could model a different path—one that aligns ecological restoration, economic renewal, and social repair.

Making the Bioregion Visible to Itself

A bioregional lens does not promise easy answers. Instead, it offers something more durable: a way of seeing that reconnects geology to culture, water to economy, and past to future. For the Genesee–Finger Lakes, this means learning to think and act at the scale of watersheds and communities, not just jurisdictions and markets.

The unfinished work is clear. Cities, towns, and counties need to be better coordinated and informed by a larger ecological vision. We need better shared data, deeper respect for Indigenous knowledge, and public spaces—physical and digital—where residents can understand the state of their bioregion and deliberate about its future. If the bioregion can come to know itself more fully, it may yet discover that its greatest resource is not any single lake, industry, or vineyard, but its capacity to learn, adapt, and care for the living system that sustains it.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)